The fear of speaking, the fear of embarrassing or differentiating oneself is less so a personal fault as it is a learnt habit; a way of life and acting that gradually cemented over time to produce the mute souls we are today.

- The Usual Suspects

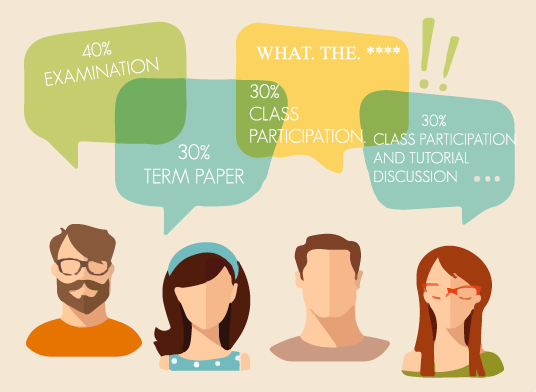

- Classroom chaos

- Participatory plagiarism

In the end, graded class participation really is a just sloppy way to solve the deafening silence of our students. No offense to those who do it out of interest and that rare, purist desire – there are often many more black sheep than white ones. We have to be forced to speak up now rather than learn from young the inherent worth of giving our voice to an often faceless system.And of course, many tutors use IVLE statistics for forum postings to decide class part on the basis of the number student submissions, not what they actually say… Without a standardised, objective rubric for computing “participation”, we may very well just be barking at the tutor for attention. Learning to speak up So why do such problems continue to persist? This being Singapore, we can almost blame everything on one thing: the education system. No longer do we have the luxury of disappearing into our seats, hiding behind classmates to avoid the teacher’s gaze and relying on our more vocal classmates to take one for the team. Yet, if we put aside our fears for just a second, isn’t that precisely the problem? The fear of speaking, the fear of embarrassing or differentiating oneself is less so a personal fault as it is a learnt habit; a way of life and acting that gradually cemented over time to produce the mute souls we are today. In Primary School, I remember with distaste that it was characterised by intense repetition. Languages were about compositions, comprehensions and penmanship. Math emphasised frequent practice of the same types of questions (i.e. drilling) and Science was about memorising definitions word-for-word.

The curricula, teachers themselves and the system encourage a pervasive mode of rote learning and memorising. Then, without warning, vigorous class part suddenly becomes an expectation.In essence, there was a tremendous amount of rote learning – a fact of life exacerbated by even-more-repetitive assessment books, and regular tuition. I called it life support because it kept me barely alive even as learning was dead. When we were nearing the exams, ten year series (TYS) became our best friends. Even if it wasn’t an absolute bore, it certainly drummed in the idea that school was a lot about practice makes perfect. Given the insignificance of class participation in one’s educational career, it comes to no surprise that many become uncomfortable with speaking up in university. Changing the context does little to change us as students. The disjuncture between largely anti-participatory public education and university is enormous in this respect. The curricula, teachers themselves and the system encourage a pervasive mode of rote learning and memorising. Then, without warning, vigorous class part suddenly becomes an expectation. Shutting out the white noise In the end, graded class participation really is a just sloppy way to solve the deafening silence of our students. No offense to those who do it out of interest and that rare, purist desire – there are often many more black sheep than white ones. We have to be forced to speak up now rather than learn from young the inherent worth of giving our voice to an often faceless system.

What are your main gripes with “class participation” in NUS? Share your thoughts with us on our Facebook page! Want to read more articles like this? This article first appeared in Issue #2 of AY2015/16. You can grab a copy right here on campus!