After a decade of silence, beloved filmmaker Hayao Miyazaki re-emerged from his fourth declaration of “retirement” to release a new film, which finally came to theatres in Singapore on 30 November 2023. As an avid Studio Ghibli enthusiast, this was amazing news. I’d never seen a Miyazaki-directed film on the big screen before, and I was waiting with bated breath to relish in a whimsical new adventure. His latest (and supposedly final) endeavour is The Boy and the Heron, which was announced with little publicity, save for a poster and trailer. So, what is the film about, and should you watch it?

How Do You Live?

The film loosely adapts Genzaburo Yoshino’s 1937 novel How Do You Live?, a story about the life experiences of a junior high school student and his uncle. At its core, the novel is about childhood, loss and humanity, themes that inspired Miyazaki’s most recent work.

In The Boy and the Heron (How Do You Live in Japan), Miyazaki weaves an intricate story with a new world and characters. Below, I delve into the themes, eye-catching motifs, and poignant scenes that stood out to me after my first viewing (as I foresee myself rewatching this film to enjoy the performances of the star-studded Hollywood cast in the dubbed version).

Going down the rabbit hole

Spoilers ahead! Skip to “Closing notes” to avoid them.

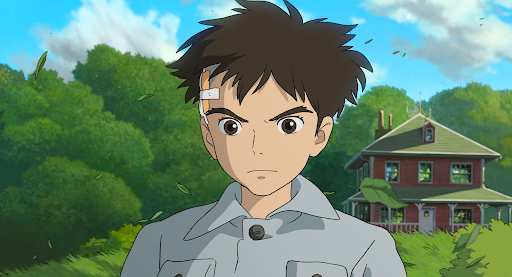

The opening sequence is striking. Blanketed in smoke, Mahito Maki’s hometown is a picture of death and disaster amidst the Pacific War. His family is in a frenzy: the hospital where his mother, Hisako, is staying was bombed. Against his father’s warning, Mahito rushes after them to the scene. Desperately weaving through ghastly-looking crowds, he runs through the ember-filled night, only for it to be too late. Cut to the title card.

Dealing with grief

A year later, his father is remarried and expecting a child with the poised and beautiful Natsuko, Hisako’s younger sister. They move into her countryside home, a sprawling estate surrounded by vibrant greenery and housing several sweet old grannies who tend to him (watching this in theatres, I was thoroughly envious of the property). Despite their efforts, Mahito stays closed off and barely speaks aside from simple civilities. At school, he is ostracised by his new classmates.

After getting into a physical altercation with them, he picks up a rock and hits himself in the head, blood gushing out profusely. Why does he do this? He dismisses it as clumsiness, even when his father insists on avenging him. A clear-cut reason would be that Mahito wanted a reason to stay home. Beneath the surface, however, is an undercurrent of unbearable grief. At only 12 years old, Mahito suffered a great loss and is assumedly coping with it on his own, reaching breaking point. As his father and stepmother have moved on with life, Mahito is still haunted by the visage of his late mother, engulfed in flames. His enduring grief is compounded by the fact that Natsuko “looks exactly like” Hisako, serving as a constant reminder of his loss. Similarly, the scar from his head injury remains with Mahito for the rest of the film, a physical representation of the trauma Mahito suffered that will stay with him as he grows.

The inclusion of war, grief and trauma in this film is unsurprising. Given Miyazaki’s experience with war and his pacifist values, his films often feature these themes in some form, be it a retelling of events à la The Wind Rises, or as a backdrop to the fantastical drama Howl’s Moving Castle. Across the board, through depictions of the characters’ involvement in war and the devastation it brings, the collective anti-war message that Miyazaki seeks to portray is glaring. All the while, themes of human selfishness and desperation are contrasted with magic and whimsy.

Major motifs: the animals in the film

The titular grey heron first appears when Mahito enters his new home, catching his eye and swooping past him. Natsuko notes that the heron has never come inside before, inexplicably tying it to his arrival. It speaks for the first time to him, cawing, “Save me!”—emulating and taunting him with the pleas of his late mother. After incessantly pestering him, Mahito confronts it by the lake. The heron tempts him to enter a closed-off tower at the edge of the estate, claiming that Hisako is alive inside and awaiting his salvation. In a trippy sequence, Mahito is then overwhelmed by an army of frogs and fish, clamouring for him to join them.

Interestingly, frogs are associated with returning to one’s place of origin, as Mahito will. As for the heron, while interpreted by some as a harbinger of death, it is also a symbol of rebirth. A solitary bird, the heron represents self-reliance, soul-searching and introspection, making it a fitting companion for Mahito’s voyage. Though they frequently bicker (the heron claims that he is not Mahito’s ally) they work together. Their unlikely friendship points to the relationship between man and nature, and between life and death. Unfortunately, we do not learn the heron’s backstory, acting more as a yappy sidekick than a fully fleshed-out character.

Herons, frogs and fish are all viewed as symbols of good luck, so despite their unsettling portrayals, they signal the beginning of Mahito’s tumultuous yet edifying journey of self-growth.

One day, Mahito witnesses Natsuko walk alone into the trees. When she does not return, he goes after her into the tower with a granny (Kiriko) in tow.

Traversing a time-bending tower

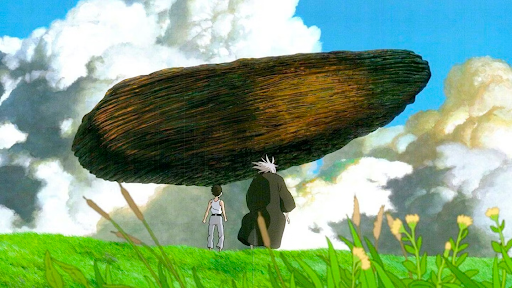

The mystical tower, constructed decades ago by Mahito’s great-grand-uncle and now covered with overgrown foliage, harbours a great mystery. It was built around a fallen meteorite, the source of its otherworldly, reality-bending properties, and now “stands straddling all kinds of worlds”. Mahito and Kiriko enter a tunnel with an inscription from Dante’s Inferno: “fecemi la divina potestate”, Latin for ‘I was made by divine power’.

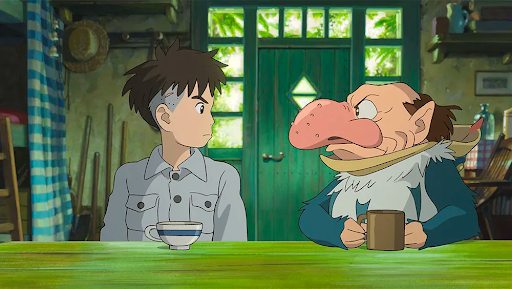

Venturing inside, I was captivated by its gorgeous design: ancient mosaic tile flooring, glittering constellations adorning the ceiling, and enormous bookshelves. Mahito encounters the Tower Master, who sends him downward into the tower (with the floor swallowing him up) to embark on his quest.

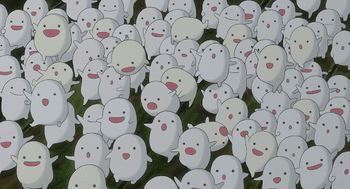

Mahito finds himself in a limbo of sorts, where the beforelife and afterlife coexist. It’s surprisingly picturesque: golden sunlight filtering through the clouds against a blue sky, green fields, and a vast ocean with fleets of ships dotting the horizon. He meets the seafaring woman Kiriko, an alternate-reality version of the granny that accompanied him. They sail together, catching monstrous fish to feed the hollow souls of the dead and the adorable warawara (souls that have yet to be born).

(Source: The Boy and the Heron)

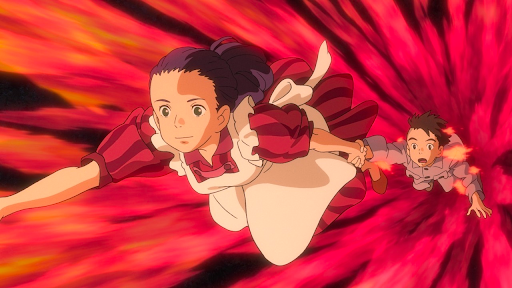

He also meets Himi, a young girl with fire powers. She saves Mahito from danger, emerging ablaze, looking much like the visage Mahito keeps seeing. So it’s no surprise to learn that Himi is a younger Hisako from another reality. Mahito and Himi ascend the tower with the heron tagging along—simultaneously evading a kingdom of (pretty cute) man-eating parakeets—to find Natsuko and the Tower Master.

I won’t go into too much detail about the second act so that you can enjoy the Wonderland-esque craziness for yourself. Instead, let’s skip to the climax.

Innocence, purity and the inevitability of chaos

The film culminates in Mahito meeting the Tower Master at the top of the tower, “heaven,” as a parakeet calls it. We learn that the Tower Master is his great-grand-uncle, who disappeared decades ago into the tower and has spent his days playing God and building a “perfectly balanced” world within the tower.

He believes that Mahito is pure-hearted, making him a suitable heir to this liminal world free of hardships.

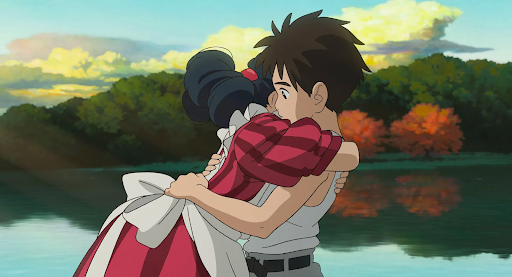

With its fate hanging in the balance, Mahito refuses to succeed his great-grand-uncle, choosing to return home to his loved ones. He refutes the notion that he is “pure”, pointing to the scar on his head. “It is a sign of my malice,” he declares. As the tower begins to collapse, our protagonists rush to the “corridor of time” to leave, where there are hundreds of doors (or portals) to different worlds. Himi approaches her door, and Mahito tries to stop her, exclaiming that she will die in a hospital fire. She responds with an assuring smile, “Fire doesn’t scare me,” and returns to her timeline. Mahito, Natsuko and Kiriko reunite with the others back home, the heron disappearing and the tower destroyed behind them. With its destruction, the rip in the fabric of the universe is sealed, ending the whirlwind journey.

This conclusion captures a recurring, nihilistic idea prevalent in Miyazaki’s films, despite their tenderness and warmth: the world is imperfect and always will be. Humanity is marked by “suffering and tragedy and folly”, yet in the face of the world’s inexorable evils, trials and tribulations, we can choose to respond with bravery and compassion, all while endeavouring to maintain childlike wonder. That’s the beauty of life. As the young Mahito shows us, his grief is wearying and tainting, but it is a stepping stone to maturity. As Miyazaki writes in Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind, “The greatness of a mind is determined by the depth of its suffering.”

Closing notes

While writing this, I read a plethora of alternative interpretations online since, naturally, its incomprehensibility is dividing audiences. Many more scenes in this spellbinding film are worth dissecting, but I’ll keep this article concise. This film is not a clear-cut, feel-good fairytale in the same vein as Ponyo. Instead, expect to leave the theatre with some lingering questions to ponder. It is as perplexing as it is peculiar, tinged with bittersweet nostalgia. The Boy and the Heron certainly feels like a touching parting gift to audiences, with scenes that bring to mind Miyazaki’s previous works. For one, the adorable warawara reminded me of the soot sprites in My Neighbor Totoro. The design of the grannies especially had me drawing parallels with grannies from other films, such as Ponyo.

Animated with the assistance of industry giants (including Ufotable and CoMix Wave Films) and a team of talented artists, the film’s visuals are nothing short of stunning. The animation is crisp and clean and flows beautifully, with each scene combining meticulously painted backgrounds with standout foregrounds in the classic Studio Ghibli style. It is no surprise that the film clinched the 2024 Golden Globe (Miyazaki’s first) for Best Animated Motion Picture.

Moreover, the film—described as “a semi-autobiographical fantasy” in the trailer—reflects numerous aspects of Miyazaki’s life and philosophies. Just as Mahito’s father earned a sizable income from manufacturing aircraft, so too did Miyazaki’s father and uncle in manufacturing rudders for fighter planes in World War II. His outlook on the world is best encapsulated in the documentary The Kingdom of Dreams and Madness. When asked about the future of Studio Ghibli, he nonchalantly replies: “The future is clear. It’s going to fall apart. I can already see it. What’s the use worrying? It’s inevitable.” He then turns his attention away, commenting, “How pretty,” and strolls off to admire the scenery.

In all, The Boy and the Heron is a touching tale of adolescence, charting one young boy’s journey to save his family as he navigates change, grief and a magical tower. The film ultimately begs the question, How Do You Live? Do we turn to escapism and idealising, like Mahito’s great-grand-uncle? Are we merely struggling to stay alive, victims of our circumstances like starving pelicans? Or, like Mahito, are we learning to embrace change, learning to live with loss and above all, ourselves?